Thud-thud. The train drunkenly swayed from side to side as the wheels clacked over the joints in the railway tracks. Out the open window, I looked into the pitch black emptiness as the dust of the Kyzyl Kum Desert rushed into my hair. This was just the start of the long journey I was taking, on a mission to see first-hand the desolation caused by one of the world’s worst and least-told environmental disasters.

The Aral Sea was once the world’s third largest inland sea. This body of water, straddling western Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, was vital not only to the remote Karakalpakstan region’s economic survival due to fishing, but also that of the Fergana Valley to the east, as the rivers which fed the sea were used to irrigate cotton plantations.

In Uzbekistan, cotton has been grown and harvested in the Fergana Valley for more than 2,000 years. This lucrative source of income was seized upon by Moscow in the days of the USSR, sending production skyrocketing as local farmers struggled to match the demanding quotas of the Soviet central bank.

The quotas had two effects: first, the Uzbek government resolved that child slave labour was the most effective way to hit the targets. The second was the massively increased demand for water to grow cotton in the east of the country. Short of shipping water huge distances from mountainous Kyrgyzstan, the only source was the Aral Sea rivers running through the Fergana Valley

This spelt the beginning of one of the darkest chapters of the country’s history. Cotton (and hence water) demand continued to rise. This was in spite of widespread Western boycotts of Uzbek cotton as rumours of slave labour crept out from behind the iron curtain.

To irrigate the cotton sufficiently, the Uzbek government, under the watch of Moscow, diverted the rivers feeding the Aral Sea. In their efforts to maximise production, little thought was given to any consequences to the Aral Sea and the communities that relied on its fish stocks for their livelihood far in the country’s west. Cotton was the absolute priority.

The Aral Sea started to dry up. As the water evaporated, the sea became more and more salty until, one day, it could no longer sustain life. Images of dead fish floating up to the lake surface were passed across the desks of senior government officials. These officials decreed that nobody should know about this unravelling disaster, let alone anything be done. Moscow required cotton and so that is what they would get.

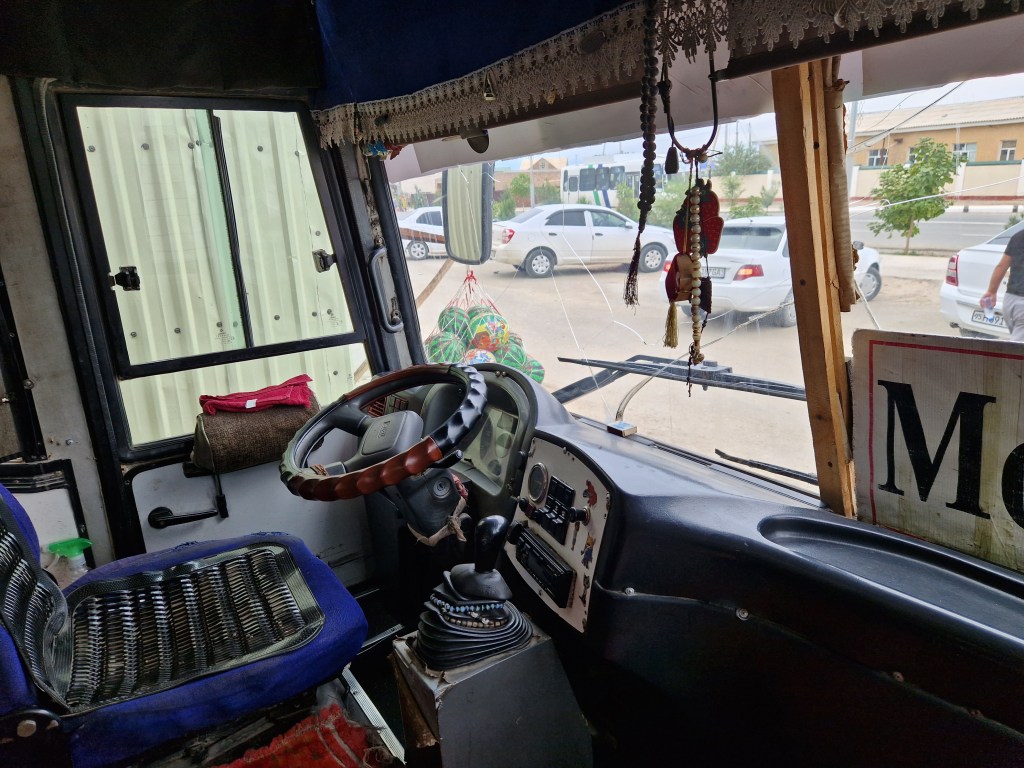

“It didn’t matter to me that the seats were ripped, the windscreen cracked and the curtains … were about as transparent as tissue paper”

Thud-thud. I was wondering whether travelling nearly the entire width of Uzbekistan, from Samarkand to Nukus, in a single night was wise. I am not a short man though here I was cramped up in a tiny bunk in the all-expense-spared platzkartny class. The daytime temperatures were in excess of 40 celsius and, though it’s cooler at night, the heat emitted by the multitude of bodies around me in the carriage meant I had a choice: boil alive or open the dangerously unrestricted window beside my bunk.

I opened the window. Refreshing, cool air rushed in though I was now terrified, with the opening being exactly at bed level, that I could have lost any number of possessions to the expansive nothingness of the Kyzyl Kum Desert. I questioned how I would make my exit from the country without a passport or navigate without a phone. Worse still, if I actually managed to get any sleep, what if I carelessly dangled an arm out the train? The occasional telegraph poles alongside the track would probably have won that battle. Still, I tried to sleep.

Between trying to keep the window shut enough to avoid falling out of the train and keeping it open enough not to boil and, miraculously, sleeping a little, I arrived at Nukus at around 6am.

I was in a daze, wondering what this new city had in store. Nukus, though, was not like the better-known, silk road cities of Uzbekistan (think Samarkand, Bukhara and Khiva). This city was purpose-built by the USSR with predictable, concrete-y, rectangular consequences.

Nukus is the capital city of the semi-autonomous Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan, a region defined by its remoteness. This remoteness was one of the key selling points for perhaps its most famous former inhabitant, Igor Savitsky, who knew it as a place so far from anywhere else that even the most dedicated Moscow bureaucrat was unlikely to know of its existence, let alone make the journey. This suited Savitsky just fine as an artist and art collector as he amassed paintings from across Central Asia and Russia, often by artists considered undesirable by those in charge.

A later visit to the museum in central Nukus which bore his name was an awkwardly contrasting experience to walking round the rest of the city. One minute, I was making my way down imposingly wide streets lined with identikit apartment blocks. The next, I was thrust into a (mercifully air conditioned) world of politically focussed art. Though this was not the Louvre in terms of the quality of the pieces, I wondered about how many sacrifices were made by artist and collector alike to create and display such pieces under such strict cultural control.

This strange interlude, though, was only another step on my mission to witness the devastating effect of the Aral Sea disaster. Nukus was built away from the former sea shore and so, having heard about how few buses run to my destination, with the desert dust still in my hair and bleary eyed, I headed to the bus station, bound for Moynaq.

A bus would have been a kind description. After the earlier train and now that I was starting to feel inhuman, it didn’t matter to me that the seats were ripped, the windscreen cracked and the curtains to keep the punishing sun out of the (un-air conditioned) bus were about as transparent as tissue paper. I had a mission and I was going to achieve it.

Much like the bus was barely a bus, the road certainly wasn’t a road. To my unexpert eye, it seemed as if it hadn’t been paved since around the 1980s, instead simply left to decay and be slowly consumed by the surrounding desert. It felt like I was travelling to the end of the world and, in effect, I was – west of here lay only dustpans left behind by the evaporating sea.

It was this dust that had forced so many to up sticks and leave the area. It was not uncommon for high winds to whip up the mix of dust and salt, creating a deadly type of sandstorm which was responsible for vastly increased rates of respiratory disease among locals. Not only had the disappearance of the Aral Sea destroyed their livelihoods but it seemed intent on taking their lives as well.

As a result of the inaccessibility and risk to health, few tourists have braved this journey. This created a feeling of curiosity among the few locals who were using the bus to Moynaq as I stepped onto it. In my best (but very broken) Russian, I said that I was English and that I had come to see what was left of the Aral Sea. All I could do after that was simply nod as they spoke back to me, understanding very little. Their faces, though, never ceased to look amazed that someone was deluded enough to come all this way, in the opposite direction to most as they left as soon as they could.

“It was a reminder of the power and, in turn, responsibility humans have, not just over the planet but also each other”

After four hours of being tossed around, trying with what little, sleep-deprived energy I had, to stay in my torn seat and field incomprehensible questions from curious locals, the bus ground into Moynaq. This was once a coastal town: I had made it.

I somehow deciphered from the bus conductor (who was the son of the driver), that this was also the only bus back to Nukus that day and it left in two hours. Whether the sixteen-plus hours of travel was worth it was beside the point. I was here now, time was ticking and, looking around me, an overnight stay was not an option.

I had arrived in what was slowly becoming a ghost town. The odd battered car trundled down a kilometre-long road lined by abandoned-looking houses and shops. When I found the local museum, the sole worker who served as both ticket salesman and security guard switched on the lights for me as I entered. I was the only one there.

Walking north through the town, I couldn’t help but wonder why this town had been left to rot by the Soviet state. It was once supported by fishing and even a level of tourism as it was popular with beachgoers. Where the coast once butted right up onto the town’s boundaries, it was now around 50 kilometres away. Life and community, it seemed, had evaporated with it.

Nothing encapsulated this better than the ship graveyard. With the receding coastline and increasingly saline waters unable to support fish stocks, fishermen had given up and left the area and, in doing so, abandoned their boats to rust under the desert salt and sun. A few years ago, some of these were collected up and placed near the town as part monument, part tourist attraction.

It was eerie, witnessing the huge consequences human actions and decisions in one area (such as the Fergana Valley in the east) could have on a completely different, seemingly independent one like here. The ecosystem was totally destroyed here, leaving behind an almost martian landscape stretching for so many miles it was impossible to see what was left of the sea from Moynaq.

This journey was tough for me, though I feel it fell into complete irrelevance compared to the suffering endured by the people forced to rip up their lives over the last 50 years else they would die of poverty or respiratory disease. All this because of factors outside of their control, happening across the country and dictated by a force thousands of miles away that likely didn’t even know of their existence. I have often found travelling humbling in many, often unexpected, ways though this was a different feeling entirely. It was a reminder of the power and, in turn, responsibility humans have, not just over the planet but also each other.