The consequences didn’t bear thinking about. As I hung there, held in place by an ice screw, ropes and harness, it dawned on me that my life was entirely in the hands of my Bolivian guides. I was entirely out of my depth, obvious now that I was hanging off the side of a glacier having completely lost my footing due to the exhaustion caused by climbing only the smallest ice cliff.

This article is the second half, following on from an article published last week. For the first half, click here.

Even so, the first full day of climbing Huayna Potosi, between base camp and the first camp at 5100 metres, was easy. This was mainly due to the complete absence of ice throughout the route, rendering crampons, ice axes and other unfamiliar equipment unnecessary. Of course, we all had to carry them up the precipitously steep, stony path but that was fine by me. More of a tough, oxygen-deprived workout than a matter of life and death.

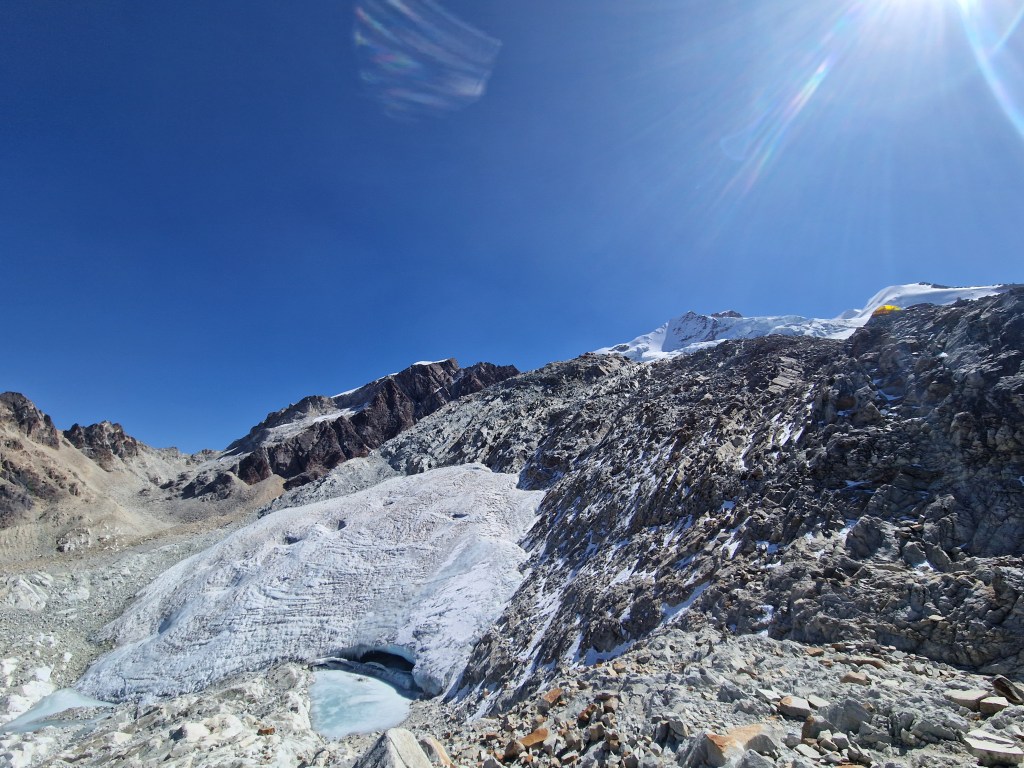

What struck me most on this shorter leg as we climbed around 600 metres was the sheer bleakness of the terrain we were crossing. This was a Martian landscape, if only less red and with the occasional evidence of snow or human life.

“I was here to climb and, perhaps crossing the line from bravery to stupidity, I didn’t voice my uneasiness”

It was rocky in the extreme and the altitude, combined with what I could only imagine were utterly inhospitable conditions during the Andean winter, prevented the growth of any vegetation at all.

Instead, the brown and rocky ground around me occasionally gave way to dirty-looking snow-capped peaks like the one I was trying to tame, as if these were the vegetation of the mountains rather than the trees at sea level. Beyond this, even the mountains weren’t able to touch one of the most brilliantly blue skies I had ever seen. It was as if being at altitude had brought me closer to space, darkening the sky into a deep royal blue which, I suppose in a sense it had.

The second, and final, campsite before the summit was somewhat basic. Even so, our guides, carrying significantly more than us on the trek from base camp, had brought enough food for a significant meal to fuel the group’s summit attempt. This was standard Bolivian fare – soup with overcooked pasta that would make any Italian scream with rage, fried chicken and rice. It wasn’t haute cuisine but I was grateful to just receive a warm meal up there.

The hut, stacked full of ancient bunks which creaked with every movement someone made lying on them, were at least comfortable enough to rest on. I even found a chess set up there and played a few games in the early evening with one of the other climbers on the expedition. The only reason why this didn’t continue later was because we had been informed by our guides that we would begin the summit attempt at midnight; I questioned whether I would be getting any sleep at all.

Before this, we were told to get into pairs by the guides to decide who we would be climbing with to the summit the following day. This was quite an important decision as each pair would be roped together along with a guide. This meant that the person you were paired with had to climb at the same pace and also have your back if things, possibly literally, went downhill. I ended up with a young Brazilian man, Antônio.

More concerningly, the guide that was assigned to us both did not speak English. This left Antônio, despite being a native Portuguese speaker, translating from Spanish into English any instructions issued to us by the man that was responsible for our safety. I cast my mind back to less than 24 hours earlier when I was hanging from the side of the glacier and a chill ran down my back. Still, I was here to climb and, perhaps crossing the line from bravery to stupidity, I didn’t voice my uneasiness at the situation.

“Wake up, everyone. It’s time to go!”, I hadn’t slept at all after turning in at 6pm. Zombie-like, we each grabbed a quick bite to eat for breakfast which had been laid out in advance of our wake up call, got dressed into the mountaineering equipment that we had been provided and threw our packs onto our backs.

There was nothing to see outside. Though we were still close to La Paz, the enormity of Huayna Potosi seemed to block any light pollution that may have seeped out of the city’s limits. The only light came from the head torches of fellow climbers. Even the moon was obscured by the now cloudy sky.

“The only indication of the route ahead was the golden snake of head torch from other expedition parties’ lights weaving their way up the glacier above”

Our guide, via Antônio’s translation, told us that the target was to reach the top of the mountain by sunrise. This gave us around six hours to climb just under 1000 metres. Drawing upon my very limited previous mountaineering experience, this seemed trivial – perhaps we could do it in four if we pushed. What I failed to consider was that we were starting this climb at over 5000 metres, higher already than Mont Blanc. It was a different sort of mountaineering entirely.

My first sensation when climbing was that of warmth. In fact, I was boiling alive in the layers I had initially put on so, as much as our guide looked on incredulously, I stopped our trio, eventually stripping down to the bizarre-looking combination of a T-shirt and ski gloves in the freezing temperatures. After a while, the guide had clearly had enough of what he clearly thought was a solid route to hypothermia and forced me to put at least my down jacket back on, which I reluctantly did.

The climbing was slow and difficult progress. Due to the darkness, it was impossible to gauge how far you had made it up the mountain and how much further there was to go, which left me in a form of mental limbo where I did not know how much longer my oxygen-depleted body would be forced to haul itself uphill, contrary to basic instinct which was to turn round and go back to the safety and comfort of the bed in the hut below.

The only indication of the route ahead was the golden snake of head torch from other expedition parties’ lights weaving their way up the glacier above and below. I felt disorientated, partly due to this lack of perspective but probably mainly due to sleep deprivation.

The strain had clearly proven too much for some. As I felt my crampons bite into the ice and snow under my feet, I occasionally glanced down beside me when I started noticing patches where the clean white blanket had become discoloured as people had vomited due to altitude sickness. Many of these people would have had to turn around, never making it to the summit. I prayed I wouldn’t join them.

Besides obscuring the struggles of previous attempts at climbing Huayna Potosi, the darkness had the additional benefit of obscuring all but the largest of chasms in the glacier we were making our way up. Once the sun revealed these to me on the descent, I questioned whether I would have willingly kept going along the ridges and past the crevasses which dropped into a black nothingness and unthinkable consequences.

Close to the summit, I could feel from the back of our trio that Antônio was struggling with the exertion of the climb. We had made good progress and were on to reach the top at sunrise, with only a tricky, narrow and icy section above the glacier to complete. My first, and admittedly selfish, thought was that I didn’t want him to ruin this opportunity for me so, with what little breath I could muster, I tried to give him some words of encouragement. Though I doubt this had much effect at all, we carried on.

As the sun was about to break through the horizon, we finally reached the summit of Huayna Potosi. I was filled with relief and pride, having survived without succumbing to altitude sickness and completed exactly what I had set out to do. Around me, I was on top of the world. The views were total, stretching for hundreds of miles in all directions. This, complemented by the beauty of a sunrise unhindered by clouds beneath or any other obstruction, was ample reward for the strain of getting there.

The experience was extremely tough, though equally enjoyable, and left me with an incredible sense of vulnerability in the face of such monolithic objects. The idea that, at any point, I may have become ill with altitude sickness or fallen into a crevasse made my experience at the summit all the more humbling, as if the mountain had allowed me to the summit rather than me making it through my own sheer will. Indeed, quite a few haven’t been as far as I got, having been forced to turn back due to any number of issues.

It was the sort of task which can put life into perspective, where all my other concerns or worries melted away in the face of a monumental challenge which I couldn’t entirely control. It required all of my focus and determination yet also compromise and balance. Even so, I felt that at any moment, the mountain could have thrown an insurmountable obstacle in my path, refusing entry to the summit. I was vulnerable, yet extremely grateful, that it had chosen on this occasion not to do so.